Neophobia has been defined as an “irrational fear” (Figure 1) and that is certainly true. The concept of food neophobia is certainly not new. However, the area and indeed concept of food technology neophobia is a relatively new idea. Perhaps I should refine that somewhat and say that food technology neophobia is not new, but recognition of it to the point where it has been named, is new. The importance of food technology neophobia prompted Cox and Evans (2008) to develop a psychometric scale in the mid-2000s to assesses such consumer concerns. This scale has been validated by Verneau et al. (2014) has been applied to assess degree of concern and resistance to various agrifood technologies by consumers, such as by Vidigal et al. (2015), who found (predictably) that concern was highest for genetic modification in food and agriculture along with applications of nanotechnology. Furthermore, this scale has been refined, abbreviated and applied to consumers (Schnettler et al., 2016). The original food technology neophobia scale has also also been demonstrated to be suitable for its intended purpose in a vastly different cultural and society context from which it was developed (De Steur et al., 2015).

This increasing prominence of food technology neophobia can be linked to the increasingly rapidity of technological advancements in the last two to three decades (Figure 2) and that food technology neophobia could be seen as something that is holding back progress in society, in the world, and curtailing implementation of scientific and technological advancements.

For example in Australia, the federal government approved commercial cultivation of GM canola in 2003 – it was the first GM food to receive approval in Australia after GM cotton has been increasingly grown since 1996. However, despite this federal approval after a rigorous assessment by the Office of the Gene Tehnology Regulator (OGTR), most states immediately placed moratoria on planting in their respective jurisdictions, with only Queensland and the Northern Territory not. This no doubt hindered progress in those early years of GM canola growth as the crop was not permitted commercially until 2008, when New South Wales and Victoria lifted their moratoria. Only last year, did South Australia lift their moratorium on the cultivation of GM canola. Now, 20% of Australia’s canola crop is genetically modified, bringing great benefits to primary producers. It has been a long and slow journey to (very) gradually increase the proportion of GM canola over non-GM canola (Figure 3). One can lament the situation and the negative impact that such moratoria had on society’s progress in Australia. It took 16 years for GM canola to be permitted to be grown in every state and territory after federal approval to do so I 2003, but at least it has happened now and the wheels of advancement in that area are moving again.

While I have detailed the situation with GM canola here, the same neophobic section tends to occur with various food processing technologies, and has been happening for a very long time. Despite the science supporting the public health benefits of milk pasteurisation, many consumers remained skeptical and indeed opposed to implementation of this life-saving technology. Today, there is great food technology neophobia associated with food irradiation in particularly. It is safe and effective (Figure 4), and the science continues to demonstrate that, but consumer resistance prevents its wide scale adoption.

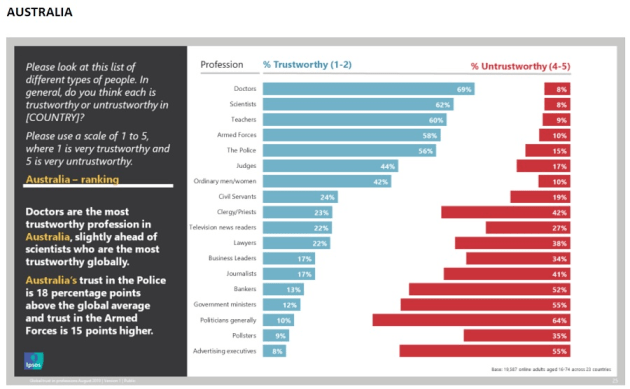

There is little doubt that the world could be in a far better place now if science and technology was allow to progress and advance society without hindrance from people’s, largely irrational, fears. There is certainly a major trust issue involved in this aspect, yet there is some contradiction. Let me explain – one result from a study (Figure 5) that I was involved in that was published in 2013 (Chan et al., 2013) was that people trust scientists (and their family GP) most when it comes to product information about food. Presumably this is because consumers see scientists and their family GP as having no conflict of interest. In general though, GPs and scientists are the two most trusted professions in Australia (Figure 6).

As one may expect, food manufacturers were considered to be the least trustworthy. So, based on this, consumers should presumably be open to listening to scientists sharing with them about the science of a particular scientific innovation and how/what the practical applications of that technology are, or can be. However, this doesn’t always seem to be the case. People still tend to be suspicious, of the technology. Is this because there is interference from government and/or food manufacturers? Or contribution to the argument from some minor advocacy groups? Perhaps both of these are true. Or is that scientists just can’t communicate in an effective, impactful and persuasive manner? Meaning, they simply can’t sell their results and ideas are scientific safety. One aspect is certain though, the science is strong and robust and it is being communicated to consumers by impartial scientists that have no link to any organisations with an interest in advancing the technology, yet people are not listening. Why is that and how real is food technology neophobia? Most importantly, as scientists, what are the most effective ways we can work with consumers to alleviate their concerns and show them the real benefits of technology innovation and implementation? This is likely to be a key to advancing society and indeed saving the world as we continue to grow in population, farm marginal lands (Figure 6) and encounter many challenges in public health.

References

Chan, C., Kam, B., Coulthard, D., Pereira, S., & Button, P. (2013, January). Food product information: Trusted sources and delivery media. In ACIS 2013: Proceedings of the 24th Australasian Conference on Information Systems (pp. 1-13). RMIT.

Cox, D. N., & Evans, G. (2008). Construction and validation of a psychometric scale to measure consumers’ fears of novel food technologies: The food technology neophobia scale. Food Quality and Preference, 19(8), 704-710.

De Steur, H., Odongo, W., & Gellynck, X. (2016). Applying the food technology neophobia scale in a developing country context. A case-study on processed matooke (cooking banana) flour in Central Uganda. Appetite, 96, 391-398.

Schnettler, B., Miranda-Zapata, E., Miranda, H., Velásquez, C., Orellana, L., Sepúlveda, J., … & Grunert, K. G. (2016). Psychometric analysis of the Food Technology Neophobia Scale in a Chilean sample. Food Quality and Preference, 49, 176-182.

Vidigal, M. C., Minim, V. P., Simiqueli, A. A., Souza, P. H., Balbino, D. F., & Minim, L. A. (2015). Food technology neophobia and consumer attitudes toward foods produced by new and conventional technologies: A case study in Brazil. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 60(2), 832-840.

Verneau, F., Caracciolo, F., Coppola, A., & Lombardi, P. (2014). Consumer fears and familiarity of processed food. The value of information provided by the FTNS. Appetite, 73, 140-146.