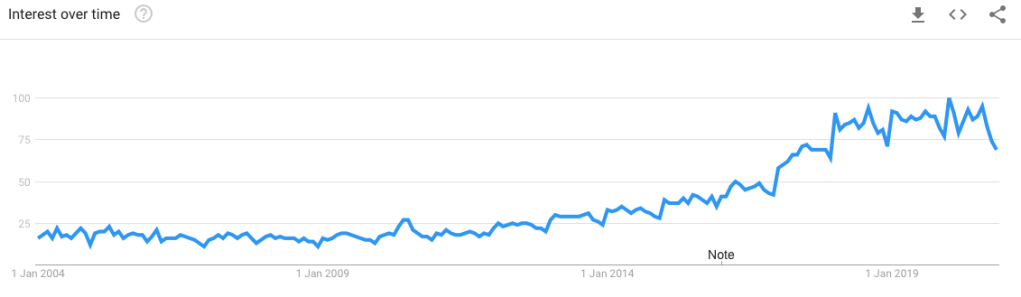

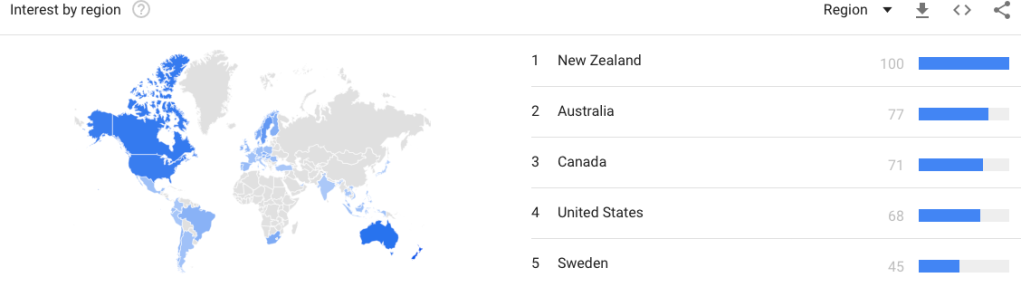

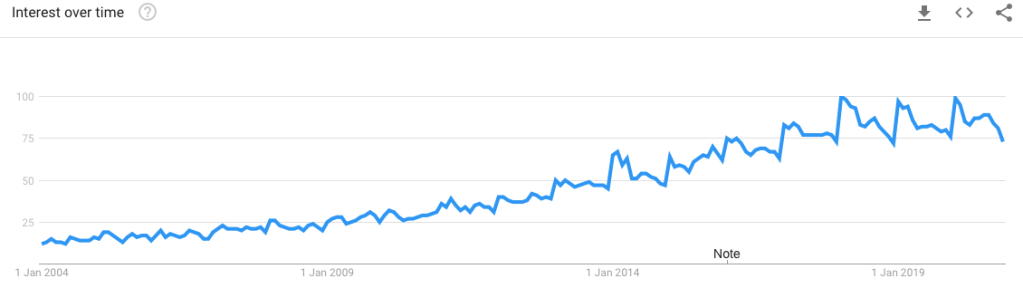

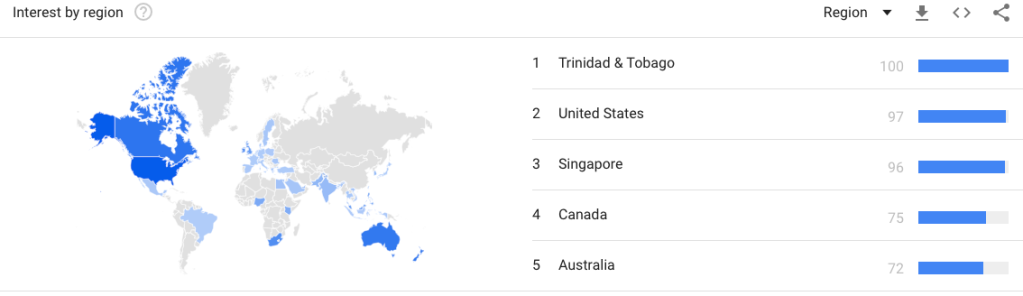

This topic is in a pretty hot space, because both kombucha and probiotics are very much ‘in fashion’ and trending at the present time across the worldwide, as can be seen in the all-time Google Trends for this word which has showed a slow rise over the last seven years, peaking this year during the third week of January (Figure 1). Leading the way in search interest on Google for “kombucha” are New Zealand, followed by Australia (Figure 2). This shows how interest in kombucha is at an all-time high in 2020, especially in New Zealand and Australia, followed by Canada and the United States. Google interest in “probiotics” has shown an increase ever since records began (Figure 3), with a peak at a similar time earlier this year (late January/early February). Search interest from Australia (5th) and New Zealand (6th) still ranks highly, although the United States (2nd) and Canada (4th) rank higher, with Singapore at number three. Perhaps surprising is Trinidad and Tobago at number one – small sample size perhaps? In any case, kombucha and probiotics are of much interest, particularly from westernised nations of the world with advanced economies.

This strong interest, resurgence is fascinating, given the age-old origins of both kombucha and provides, essentially stretching back millennia for kombucha in particular. At this stage I want to introduce the distinction between probiotic foods and beverages and fermented foods and beverages. While there is certainly overlap, in many instances, they are certainly not interchangeable terms. Let us just consider that all foods/beverages could be categorised as:

- Fermented and probiotic – for example most yogurts and kimchi.

- Non-fermented and probiotic – for example some popcorn and some protein bars.

- Fermented and non-probiotic – for example natural kombucha and sourdough bread.

- Non-fermented and non-probiotic – for example peanut butter or ice cream.

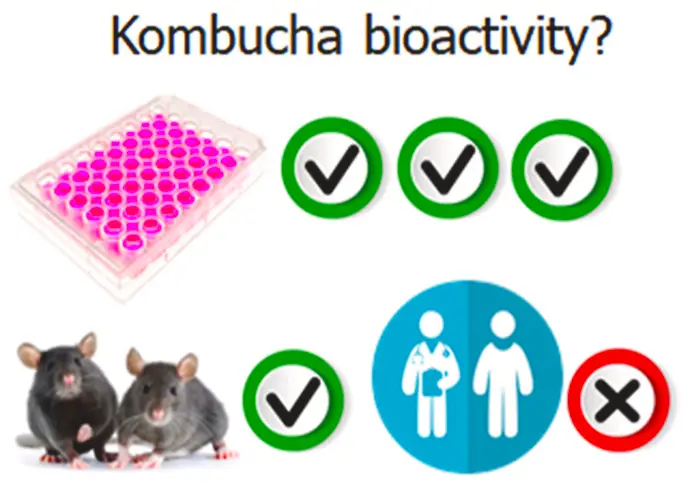

Kombucha is naturally, a fermented and non-probiotic beverage (tea) of ancient Chinese origin with consumption for “magical” properties being known from the Qin dynasty (around 220 BC) with subsequent historical consumption in China, Germany and Russia (Greenwalt et al., 2000). However even today, despite mass consumption as a functional food for various postulated health benefits, no real evidence of any health benefits exists in the human context in vivo although promising results have been seen in vitro and with animal models (Figure 5) (Morales et al., 2020).

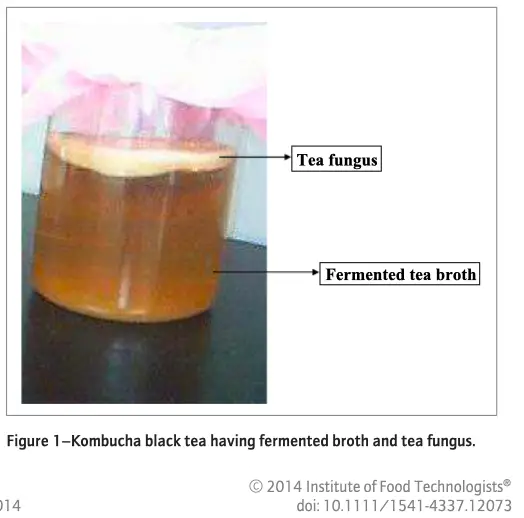

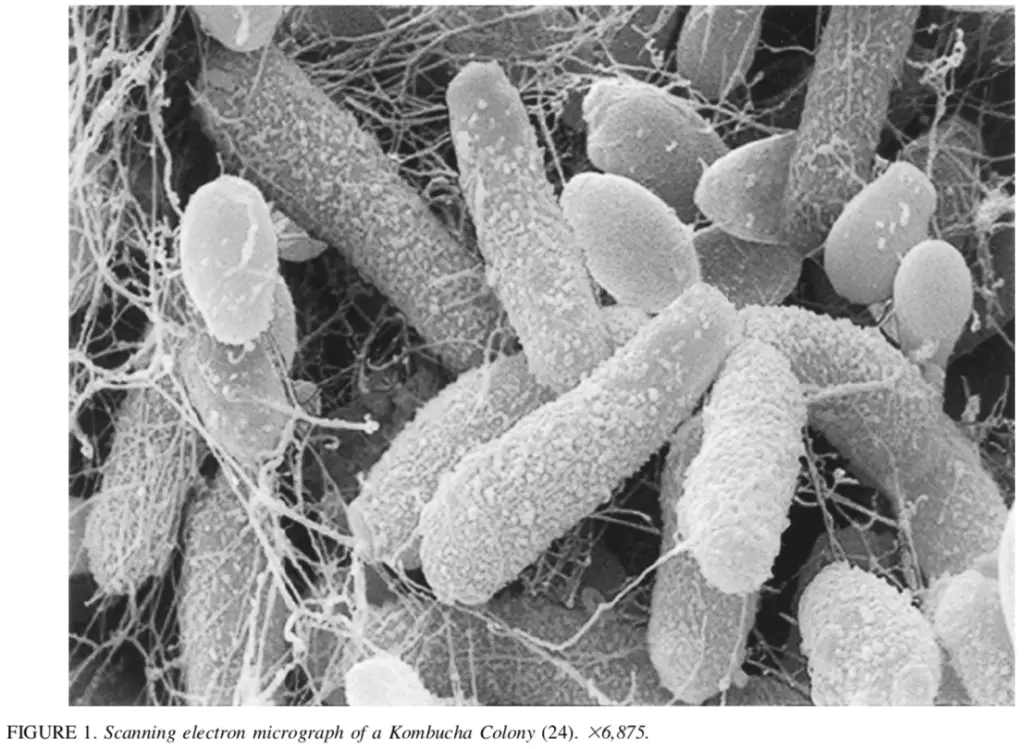

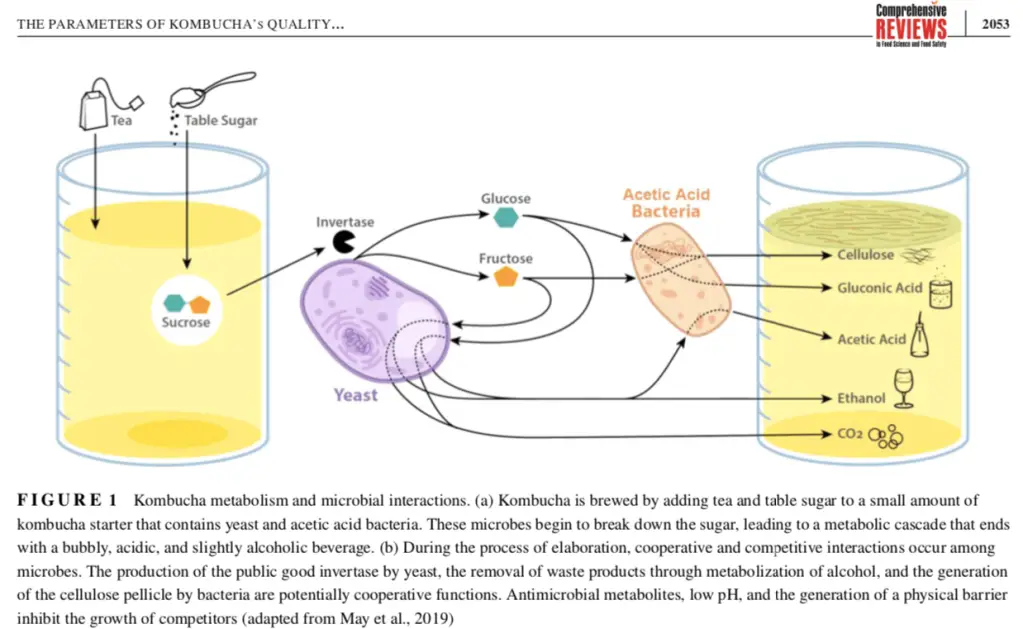

Kombucha is produced by what is referred to as a SCOBY, a Symbiotic Culture Of Bacteria and Yeasts and is widely known in consumer circles as “tea fungus” (Figure). Within this symbiotic community (Figures 6 and 7), bacterial diversity is limited to mostly species of Acetobacter while a myriad of yeast species are likely to be present (Teoh et al., 2004). A detailed review by Morales et al. (2020) has identified the following microorganism groups isolated from kombucha; 22 species of acetic acid bacteria from six genera, 3 species of lactic acid bacteria from two genera and 41 species of yeast from 21 genera – Acetobacter and Gluconacetobacter are the bacterial genera with the most species isolated from kombucha while Hanseniaspora and Zygosaccharomyces are the yeast genera with the most species isolated.

So, while kombucha is indeed a fermented beverage, it is not fermented with probiotic microorganisms – it is fermented with yeasts and acetic acid bacteria that do not have any demonstrated probiotic benefit. Therefore, their only role is to turn tea into kombucha through their growth and metabolic activity, thus producing a variety of compounds in the process (Figure 8). Thus, while you may in fact be consuming live culture in kombucha, these microorganisms that have been used to make kombucha will do little for your gut wellbeing. From studies conducted on the microbial content of kombucha, there is admittedly some lactic acid bacteria present sometimes, however while they MAY be probiotic, they are most likely present at too low a concentration to confer any health benefit to to the host, which is of course a key element of the World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of probiotics.

Manufacturers have thus sought to capitalise on the probiotic image of kombucha through the addition of probiotics to the product, that have no role in actually making the product. This is fine, but it’s worth knowing that such probiotics are an additive because as mentioned above, they do not function in the fermentation process. Therefore, from this perspective, kombucha has little difference from any other probiotic food or drink to which probiotics are added, to make them probiotic products, of which there are diverse types on the market these days, such as popcorn (Figure 9).

Last point, read the science, believe the science and remember to only trust credible sources so as not to be misled by erroneous information that is more easily found online (Figure 10). While kombucha might be delicious, they are not naturally probiotic and need to be made probiotic through the addition of probiotics (therefore, read the label and see if it is probiotic or a fermented beverage only) and there is certainly no robust evidence that kombucha has any human health benefits, despite such claims below in the popular health media online.

References

Greenwalt, C. J., Steinkraus, K. H., & Ledford, R. A. (2000). Kombucha, the fermented tea: microbiology, composition, and claimed health effects. Journal of Food Protection, 63(7), 976-981.

Jayabalan, R., Malbaša, R. V., Lončar, E. S., Vitas, J. S., & Sathishkumar, M. (2014). A review on kombucha tea—microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 13(4), 538-550.

Morales, D. (2020). Biological activities of kombucha beverages: The need of clinical evidence. Trends in Food Science & Technology 105 : 323-333.

Teoh, A. L., Heard, G., & Cox, J. (2004). Yeast ecology of Kombucha fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 95(2), 119-126.

Tran, T., Grandvalet, C., Verdier, F., Martin, A., Alexandre, H., & Tourdot‐Maréchal, R. (2020). Microbiological and technological parameters impacting the chemical composition and sensory quality of kombucha. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 19(4), 2050-2070.