Society’s shift away from nomadic lifestyles to plant/animal domestication and urbanisation

It is generally acknowledged that the first agricultural revolution began around 10 000 BC with the domestication of animals and plants, before which time, society practiced the ‘hunter gatherer’ lifestyle of hunting animals and gathering fruits/vegetables for short term, often daily consumption. This involved simple food preservation techniques by individuals and families, like drying (Figure 1) and fermenting, which extended the availability of their own stock of fresh foods. However, with the second (British) agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution, in particular, came urbanisation and the need for longer, commercial-scale safe storage of food. This was because the distance from production to market grew significantly, as cities grew, which were typically located some distance from rural areas of food primary production. Furthermore, this need for increased safe storage of food on a commercial scale also enabled the manufactured food industry to develop thermal processing, such as canning, which is also a way that food can be stored for long(er) periods of time. However, we now increasing are aware of the negative aspects of thermal processing on organoleptic and nutritional quality. While thermal techniques remain the mainstay of food processing, newer non-thermal technologies are gaining ground, such as high pressure processing (HPP). From hunter gatherer nomadic lifestyles to high pressure processing – looking forward to seeing what exciting developments the world of food microbiology has in store.

Food quality and spoilage

The ultimate reason for food preservation and the need to safely store food is because it “goes off”. We are all familiar with the concept of food “going off”, with mouldy bread and fruits or slimy meat (Figure 2) for example. Although these are, by and large, the more commonly encountered causes of food spoilage, there are others. For example, lumpiness (age gelation, which results from specific protein complexes forming) or sedimentation in UHT (long-life) milk (which results from enzyme action degrading the protein) or the white (or pale yellow) coloured pineapple juice (resulting from ultraviolet light stimulated degradation reactions of the colour compounds). Food preservation is generally concerned with the maintenance of the quality of food, and consequently to prevent its spoilage and ultimate contribution to the significant (and growing) food waste problem.

Foodborne disease and food safety

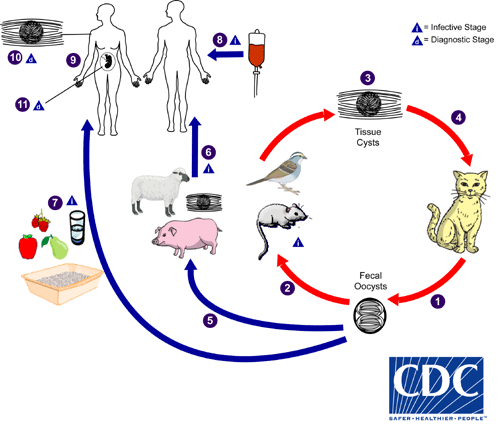

What is regarded as foodborne disease can be caused by a variety of microorganisms, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic. These types of microorganisms tend to cause foodborne disease in characteristic ways from characteristic foods. Due to the way and ease with which foodborne viruses tend to be spread, they tend to be the most common microorganisms. The faecal-oral route, common with foodborne viruses such as Rotavirus that causes diarrhoea, is a commonly occurring, and easily preventable, means of transmitting foodborne disease. Pathogenic bacteria are widespread in the natural and artificial environment, grow well in many foods and thrive at temperatures typical of temperature abuse of foods. Yeast and moulds, although more widespread than bacteria, grow slower than bacteria and tend to be outgrown by bacteria, except in high acid and low water activity foods -intrinsic product parameters which will largely inhibit bacterial growth. Protozoan parasites and parasitic worms are even less common, as they usually have complex life cycles (Figure 3), sometimes requiring multiple hosts. They also grow more slowly (than prokaryotes) and have quite narrow requirements for growth parameters.

Expiry dates: The difference between Use By and Best Before

A vital distinction to know is the difference between Use By dates and Best Before dates (Figure 4), and how this relates to shelf-life. To start with though, a common misconception is that unsafe food is somehow different in taste, smell and so, from safe food. This is almost certainly never true – if that was the case, few people would contract a foodborne disease. The fact is that the unpleasant changes you see or smell in or on food, are most often the result of the growth of spoilage microorganisms, which are typically harmless. Yes, it might be unpleasant to consume some of them, but they won’t make you sick. They are not pathogenic and have no way to cause disease. The onset of these unpleasant changes with food can signal the end of shelf-life. In practice, it is usually subtle quality changes that happen before then, that determine a Best Before date, such as a reduction in crispness of a potato chip, or the way a sauce flows out of the bottle or the reduced carbonation of soft drinks. The Use By date on the other hand is all about safety – after the Use By date, that food is considered unsafe to eat, and should be discarded. This is on contrast to the Best Before date, after which, a reduction in expected product quality may be apparent, but the food or drink will still be perfectly safe to consume.