An introduction to the relationship between microbiology and the big global issues of our time. Microorganisms are indispensable to the human existence. Although less in the spotlight, the beneficial effects of microorganisms for various aspects of human endeavour cannot be underestimated. Life as we know it would not be sustainable without the contributions of a myriad of microorganisms. From the global diversity of fermented foods produced by microorganisms to the probiotics that contribute to ensuring a stable gut microbiome for a range of personal health benefits, from gut health to mental health, microorganisms are the cornerstone of humanity’s success. Furthermore, there are indirect benefits to our food supply, through the positive contributions microorganisms make to agriculture, from livestock probiotics to regenerating soil and reducing crop reliance on traditional pesticides, the array of benefits and their significance is staggering. As a global society exploring options to address the significant challenges of our time, the importance of microbial contributions to human activities is likely to increase. As crises associated with climate, environmental damage, population growth, infectious disease outbreaks, food insecurity and more increase in prominence, the world is likely to turn microbial-associated solutions. From supply of nutritious foods and combating infectious diseases to bioremediation and regeneration of agricultural land, microorganisms have demonstrated their wide-ranging potential. Thus, the key to longevity of humanity on this planet, and maybe even colonisation of other planets, could very well lie with unlocking the secrets of known, and yet to be discovered microorganisms. There is an immense amount we are unaware of, in the microbial world, in fact, we may even be ignorant to what we don’t know. Consequently, microbiology stands at the edge of an very exciting period, with food microbiology in particular, being on the verge of contributing much to enable humanity to overcome some of the greatest challenges ever faced – we just need to further tap into the richness of the microbial world and harness it’s treasures in a way that brings harmony to the biosphere.

If we first look at antibiotics – there’s no doubt over the significance for humanity of antibiotics. The chance discovery in 1928 (Fleming, 1929), and the subsequent trials and commercialisation that led to penicillin use during the first world war no doubt started a revolution in public health. No longer were many bacterial infectious diseases to be feared to the extent they once were. Penicillin changed the course of medicine (Gaynes, 2017) and there’s no doubt that the world was never the same during this antibiotic era compared with before. Reductions in illness and death along with increases in longevity have changed the face of society as antibiotic use became routinely available across the globe. As with many tools, when they are used for their intended use, little harm occurs and any risk or hazards can be more easily managed. Antibiotics are meant to either stop the growth of invading pathogenic bacteria, thus giving the host’s immune system a better chance to combat the infection or go one step further and actually eliminate the invading pathogenic bacteria, on behalf of the host’s immune system. Antibiotics should not be used routinely and/or regularly (except in rare and exceptional circumstances) and definitely should not be used in a preventative capacity. It is therefore important to remember some key points; I) Antibiotics are part of natural microbial defence mechanisms, II) Antibiotics can act as broad-spectrum (effective against a wide range of bacterial species) or narrow-spectrum (effective against a limited range of bacterial species), III) Bacteria have short generation times and therefore can undergo rapid mutation, IV) Gene transfer between bacterial species to facilitate the dominance of beneficial phenotypes can occur frequently.

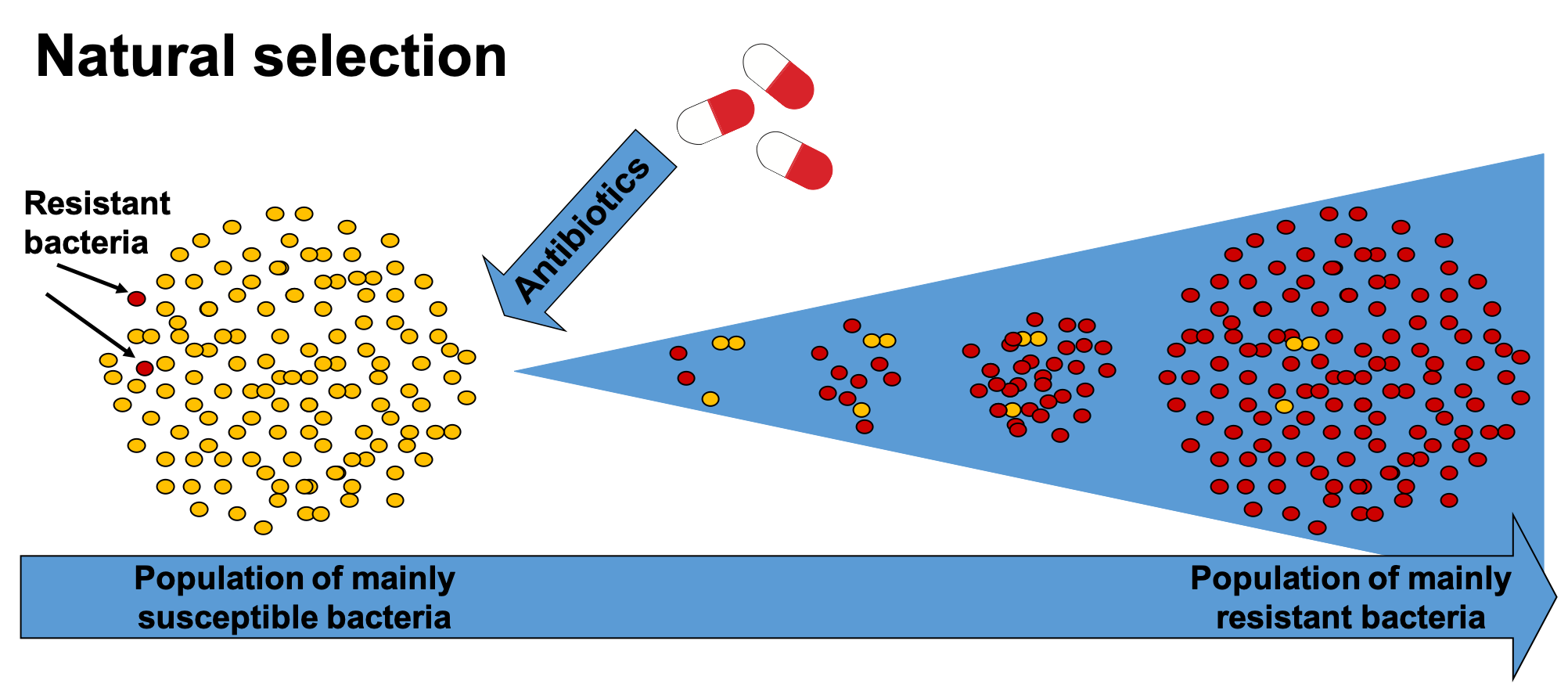

Overzealous prescription of antibiotics, in combination with the demanding attitude of some patients and those patients that don’t follow antibiotics’ instructions for use, certainly contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance and damage to the human microbiome. However, it is excessive veterinary use, or misuse, of antibiotics in agriculture, which is potentially more cause for concern. Legitimate use of antibiotics for control of active infections, as is the case with humans, is one thing, but when antibiotics are used to prevent infections in livestock and then for other growth promoting purposes in animal-based agricultural systems, then that is bad news. Antibiotics were never designed for routine prevention use, and should never be used in this way. Why is this? When there’s an environment where antibiotics are constantly present, that becomes the norm. This will select for bacteria that are able to grow better under such conditions, meaning the constant presence of antibiotics will select for antibiotic resistant bacteria – that’s just the way nature works. Antibiotic resistant bacteria, or better put, bacteria containing genes, either on their chromosome or more typically plasmid-borne, for antibiotic resistance are clearly going to be at an advantage over those bacteria that don’t have such genes. It is worth reiterating that antibiotic resistant genes are always present, but under normal circumstances, without the (constant) presence of antibiotics, bacteria which have such genes are at no selective growth advantage over those bacteria that don’t have such genes. Therefore, such bacteria remain at a consistently low proportion. With increasing exposure to antibiotics, the bacteria that do not have antibiotic resistance genes will be less competitive in such an environment and start to die off at a greater level, reducing in proportion as the selection pressure favours those bacteria with antibiotic resistance genes. As exposure to antibiotics continues, the scale tips more and more in favour of bacteria that possess antibiotic resistance genes, which increase in proportion in that population.

References

Fleming, A., 1929. On the antibacterial action of cultures of a Penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzæ. British Journal of Experimental Pathology 10:226-236.

Gaynes, R., 2017. The discovery of penicillin—new insights after more than 75 years of clinical use. Emerging Infectious Diseases 23:849-853. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2305.161556